Setting goals is a lot more common than achieving them. This is in part because of how we set our goals, and in part because of how we check-in on our goals and hold ourselves accountable.

It’s important to know why we’re setting goals, so that we have a sense of commitment and motivation to achieve them. Then we need to make goals clear and measurable, and work backwards to define leading indicators and milestones. Lastly, we need to define a cadence of accountability so that we can evaluate how we’re doing and make behavior modifications along the way.

We’ll go through both personal and work examples, and end by reviewing goal trees for setting goals in larger organizations.

Take a snapshot

I’m a fan of goals anchored in visceral emotion and vivid imagery. It helps to create a bit of drive. Envision the future outcome you want and imagine yourself in a visual picture of that outcome. Maybe you want to be in great shape — explore to see if there’s some visualization, like being in super great shape on the beach and feeling confident. Maybe you want your startup to grow its revenue by 10X — maybe there’s some annual party and the end of 2021 and you’re all toasting to the success. Maybe you’re working on a new drug or healthcare project, and there’s a way to visualize the impact on saved lives or quality of lives. Visualize yourself in the goal state, getting whatever it is that you want to get out of achieving your goal. Getting in shape or tripling your revenue aren’t ends in themselves, they are means to ends — visualize the endgame.

The snapshot answers why you are setting these goals. It’s not something you measure, it’s the reason why this is worth measuring.

Set measurable top down goals

Let’s say you’re setting goals for an entire calendar year. Start with the outcomes you want, and then think about how to make them measurable.

Define your goal at a high level, but keep drilling down until it’s clear and measurable.

The process for personal and work goals is the same, and I write mostly about startups so let’s switch it up a bit since we’re just now kicking off 2021. Let’s start with a classic personal fitness goal. Suppose you want to ‘get in shape’ by EOY 2021. This is a great starting point for a goal, but it’s not a goal. A goal needs to be “X to Y by WHEN” — the goal must be expressed as a number, and you then must start with an explicit statement of today’s value of that number, the target number, and the time period you are setting the goal for.

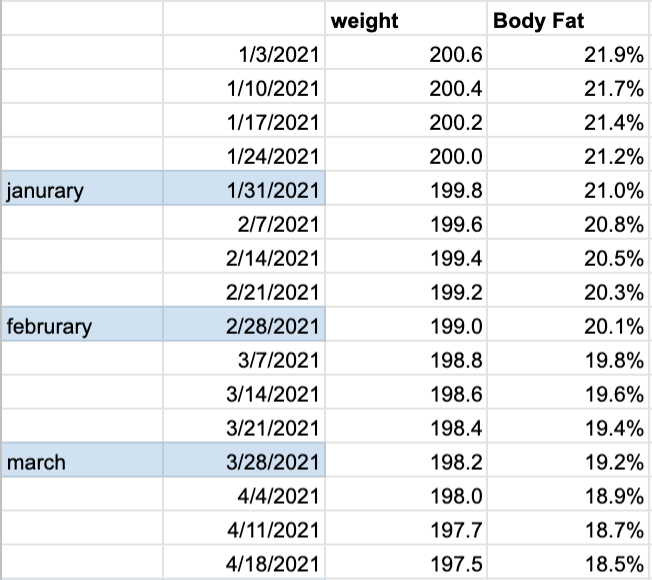

Getting in shape isn’t measurable, and can be refined in many ways. You need to refine more clearly what this means for you. I had a couple injuries in 2020 that set me back on my fitness goals, so I got in significantly worse shape the second half of the year. I know that I want to recompose my body so that I lose weight overall but I cut body fat dramatically and add muscle. I Bought an inexpensive scale that approximates body composition, and I’m starting the year at 200.6 pounds and 21.9% body fat. I set a target to get to 190 and 10% body fat by EOY 2021.

Here’s what the first quarter of 2021 looks like in my milestones spreadsheet.

Establish leading indicators and milestones

Now, this milestone tracking is measurable but it’s a lagging indicator of lifestyle changes that drive changes in body composition — which is a function of exercise, and calories coming in vs calories being burned.

Setting leading indicators is much harder than setting quantifiable top down goals! This is where the magic happens that separates people that achieve their goals from people who always set the same goals and never get there.

Let’s take this fitness goal as an example so you can see the degree of rigorous thinking required to set good leading measures.

First, I’ve worked with nutritionists and trainers over the years, so I know what my issues are. When it comes to nutrition, my big issue is that I skip breakfast, go straight into work, take a late lunch, and then get low on blood sugar later in the day. Then I crash hard and eat a massive late dinner and loads of junk. When I follow the discipline of breakfast every day, I don’t have the blood sugar volatility which has a huge positive impact on my mood stability and my nutrition. So for this year, I’m not counting macros or setting other dietary restrictions, I’m just setting the goal to have breakfast. Furthermore, I’m not expecting myself to nail this perfectly 7 days a week from week 1. My goal is to start at 3 days a week in Jan, and get to 7 days a week by EOY 2021. This is robust, practical, and easy to track. I’ve arrived at it through careful analysis. I don’t need to carefully count my macros at every meal, especially given my running.

I also have a goal to be able to summit the nearby mountain from my house, which is about 26 miles and 6K feet elevation change. I’m an active runner but starting from a pretty low baseline again, so I’ve build milestones leading to this outcome by increasing my running volume by 10% every 2 weeks, starting from 10 miles a week and getting to 40 miles a week by August 1, which means my long runs will be 20 miles and my heart and lungs will be conditioned for the summit effort in the fall.

Given my goal to gain muscle, I also need to workout in my garage gym at least 4 days a week, and ensure my protein intake is sufficient. I love working out, and I’ve used weight protein for years, so I don’t feel the need to set goals on these fronts.

Note the practicality — I’ve taken my overall fitness goal and broken it down into goals for breakfast and running, but I haven’t set goals for things I don’t need to, so I have less tracking to do, and my system will be more robust. Be honest with yourself though!

If you set goals with way too much detail that are way too tedious to track, then you will stop tracking them and give up on your system, and surely fail to reach your goals.

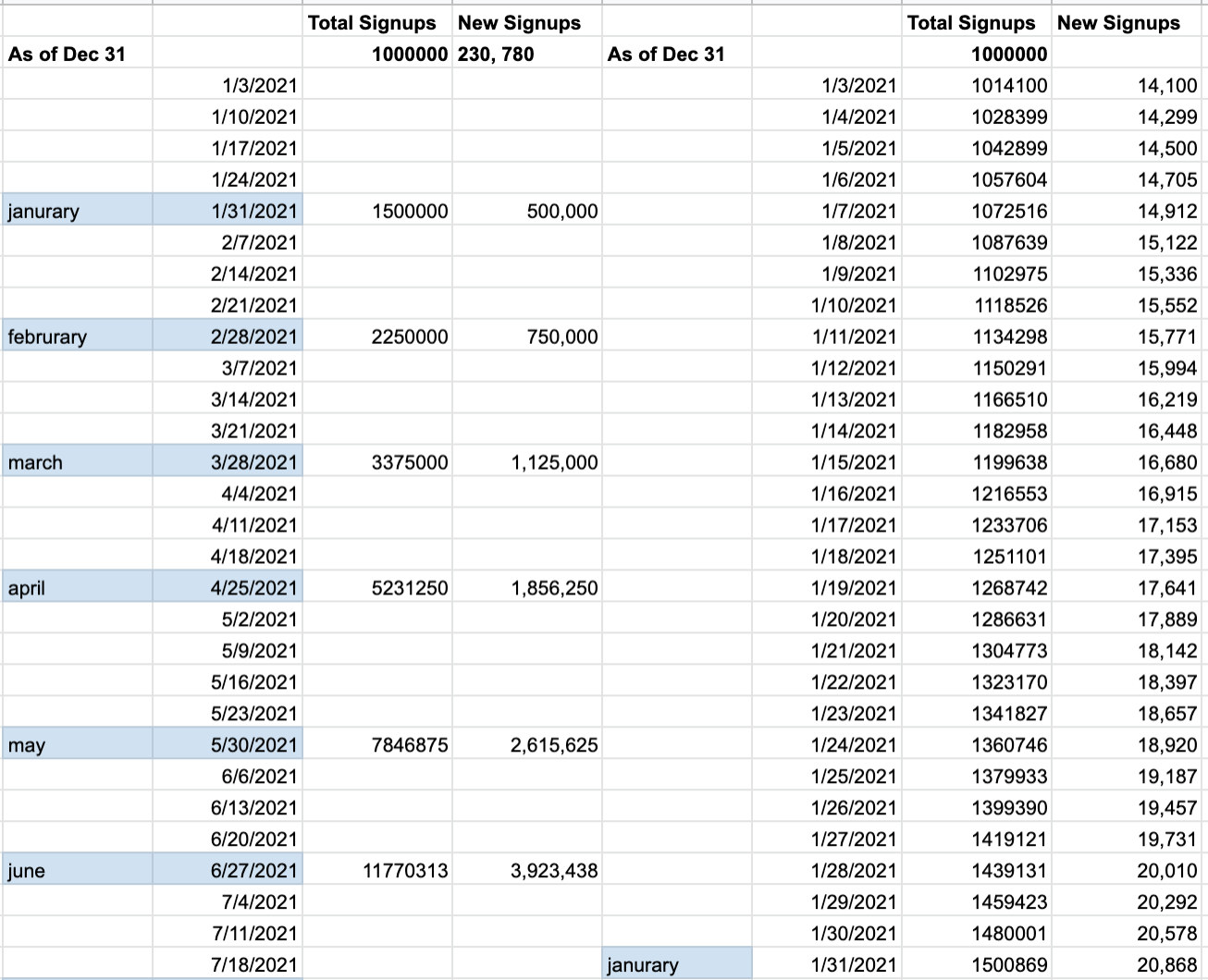

Let’s look at a couple work examples. Let’s say I’m running a seed stage startup and I want to grow revenue enough to do a big Series A fundraising in the second half of 2021. Well, first I need to go to the VCs I want to raise money from and ask them how much traction they’d expect to see in order to fund me. Suppose I do this and some give me numbers that are 4X the traction I have today, and others give me numbers that are 20X the traction I have today. Several are in the range of 10X, and that’s a number I feel like I can do based on the growth rate of the past year. We’ve been growing at 30-40% month over month, and I think we can get it up to 50% from January onwards, and if we do that 6 months in a row we’ll have growth 10X by mid year.

So I’m setting my goal to 10X growth by mid year, and my leading indicator is my monthly growth rate, but I’m going to measure my weekly growth rate and my daily signups. I break down my monthly growth rate into a weekly rate, and I build a table all the way down to the granularity of daily signups. This way I can track daily signups every day, and I can act on that very fast moving leading indicator along the way. So I break the 10X goal over 6 months down into roughly 50% growth per month, and then I further break it down into growing about 1.41% every day in January because I only have 28 days. Break things down in whatever way you feel comfortable, maybe you don’t want daily compounding in january and you just want a target of 17,860 sign ups every day in january, or just make it 18,000 to be round. Even though maybe you’ll be a bit lower at the start and larger at the end, if you have short enough time periods this won’t matter much. Make it easy for yourself and avoid false levels of precision that don’t help you track, or being too rough that it doesn’t let you steer.

Define a cadence of accountability

A common fail pattern is setting milestones in the first week of January, and then checking on them the last week in December. I think we all know how that’s going to turn out.

I have to commit to the discipline of tracking my leading indicators on their respective timescales and defining check-in points along the way. This is why it’s so important to make tracking my leading indicators robust and easy. If I fall off tracking and checking in, then I lose the feedback loop of accountability, and I’m very likely to fall off track from my goals.

Falling off your tracking means falling off your goals.

You should be doing a monthly check-in at a minimum for work or personal goals. Better yet, there are some things you’re even recording and checking in on daily and weekly. The faster the feedback and more frequent the check-ins, the greater the accountability and the higher the odds of achieving your goals when the end of the year rolls around.

Personally, I really like to do Sunday night checks. It’s an important way to reflect on the past week and prep for the upcoming week. When I stick to this cycle, I perform much better in life and work, and when I abandon it, I invariably lose my way and fall off my goals. So I recommend a daily or weekly check-in if you really want to take your goals seriously. Let’s take my breakfast example — if I check-in every day, I’ll know how many times I’ve had breakfast this week so far, and if I’m on thursday night and haven’t had breakfast but I have a goal of 3X per week, then I still have Friday, Saturday and Sunday and I can still hit my goal. Even if I was so busy that I skipped my check-ins tuesday and Wednesday, I still got it in on Monday and Thursday, and I still have time to act to modify my behavior and hit my goal for the week. If I checked in on this goal monthly, and had only had breakfast 3 times in the entire month, then that’s a much worse outcome and will be much harder to modify my behavior for the following month. If I’m supposed to eat breakfast 4 days a week next month and I did 3 times in the entire previous month, then I’m going to have a really hard time with this radical behavior modification next month.

Steady progress is key. If you keep a cadence of accountability and make many small behavior modifications along the way, you can move mountains, but if you check-in infrequently and then need to make massive behavior modifications, you can barely even bring yourself to move your butt out of your chair.

Although daily or weekly check-ins are important for tactical execution and behavior modification, it’s equally important to make strategic modifications every month or every quarter. Let’s suppose we’re back in the startup example aiming for 10X growth in the first two quarters of 2021. We’ve been missing our daily signup target, and we hit January 31 and our growth rate is stabilizing at 30%. We’re trying different marketing strategies, but we’re not able to drive the jump from 30% to 50% month over month growth that we thought we could, and our efforts to boost daily signups haven’t worked consistently.

Although we did a good job breaking down the overall growth goal into daily signups, we had a baked in assumption that our hypotheses about driving more daily signups were right. We tested a bunch of those hypotheses but they were wrong. This is telling us that our hypotheses about how to act on leading indicators were off. Indeed, we’ve learned that tracking daily signup probably isn’t a good leading indicator for us, we need some more fine grained things to measure that let us get down and debug why our marketing ideas aren’t connecting. We do some attribution analysis to see which channels new signups are coming from, and which campaigns are performing vs underperforming. We notice that only two of the three channels we’re using are showing mild improvements in signups, and the third is actually falling off. We decide as a team to give up on the underperforming channel and try to get a new channel that’s actually growing. So we split up the team’s focus — half will work on testing hypotheses in the two channels where we seem to be able to grow signups a bit, and the other half will work on quick prototypes of small product and messaging tweaks for two new channels that we think could work. Although the daily signups target is still there in the background, it becomes more of a lagging indicator now, and we set new leading indicators for each of these two teams — we want to get ⅔ of the target daily signups form the two channels that are working, and ⅓ of the target signups from one of the new channels we are testing, and then these two teams set their own goals for how to drive their signups — for example the number of test campaigns they run every week, or the number of product prototypes they ship into new channels in February. The teams have autonomy to do what they think is going to move their signup number, and we’ll come back to reflect strategically at the end of February.

Build goal trees for teams

For organizational goals as described above, it’s important for leadership to facilitate how high-level goals break down into smaller goals for teams and ultimately individuals. At each team’s level, the leadership at the level up is defining some top down measurable goals, and providing the team the autonomy to define how they intend to hit those goals and what their leading indicators are. Then the team’s leadership will review, debate, and sign off when they feel comfortable with the bets the team plans to make. Like the example above with one of three marketing channels drying up and forcing a reshuffle of leading indicators and a plan to enter new channels, we don’t always know what is going to move the needle on the longer term goals.

Leading indicators are bets. Expressing our best guess at leading indicators and checking in on them is a form of betting with our time and resources, and then checking in to see how the bets are paying off.

The most important way in which leadership creates autonomy and agency for its teams is in letting them take ownership of the bets they make. Leaders should for sure provide input, and they should review and sign off since they will be accountable for the bets at a higher level, but it’s important that they step back and create space for the team to define and place their bets.

Top down goal trees create more space for ownership, not less.

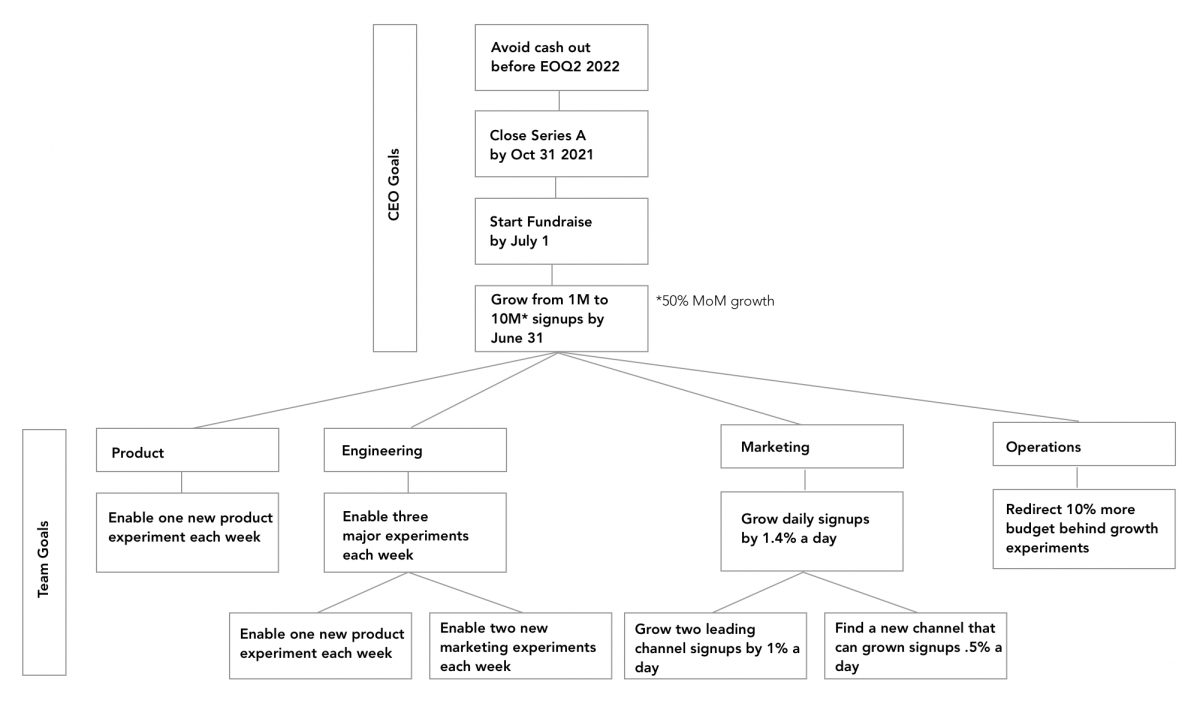

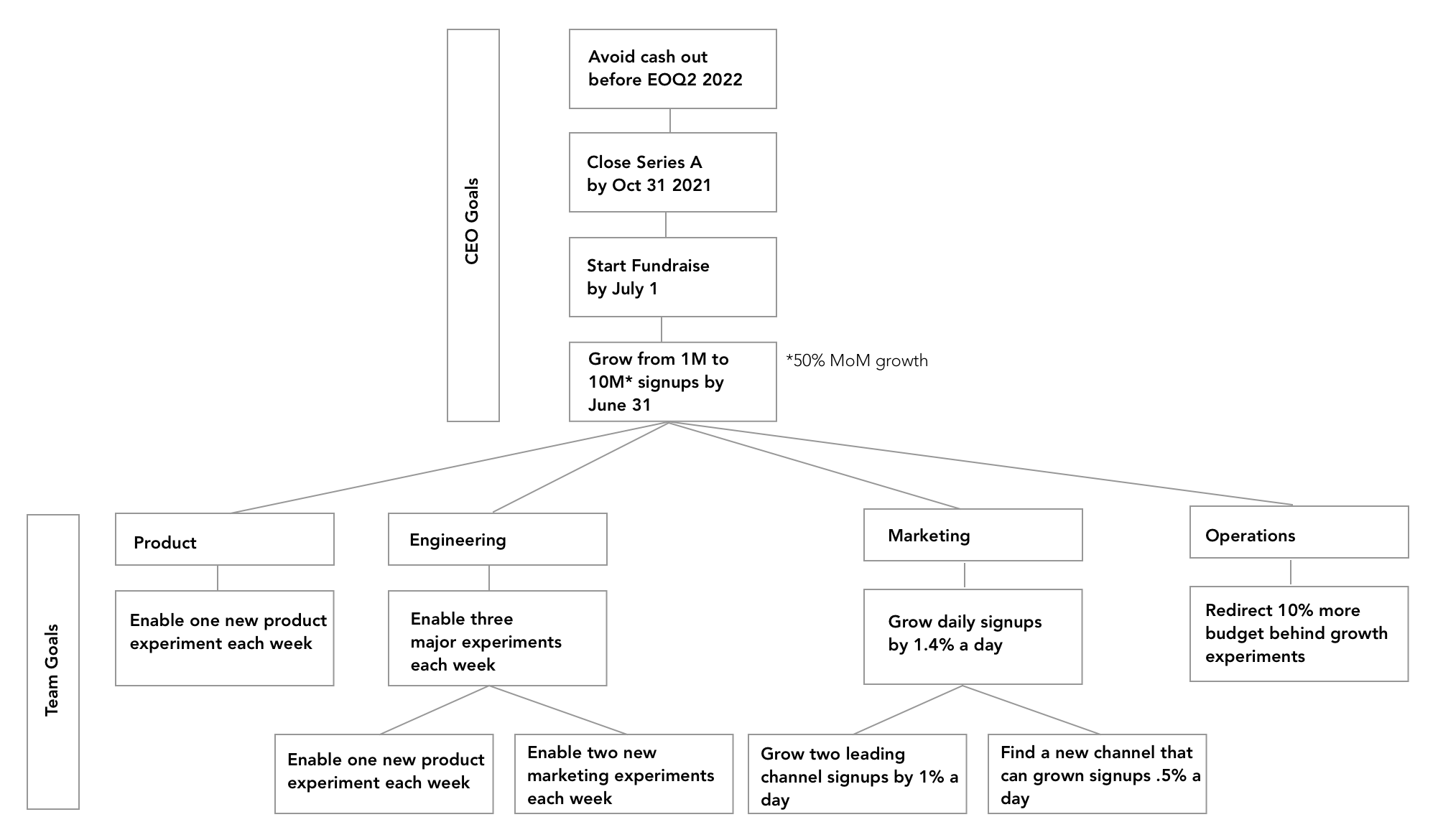

A goal tree is just a simple hierarchical tree structure showing goals at different levels in an organization. Let’s come back to the startup trying to grow 10X in the first 6 months of 2021. The reason for this goal in the first place is to run a successful fundraising in the second half of 2021, and the reason to run the fundraise is that it’ll run out of cash in Q1 2022. This is important context for the CEO — if we fail to hit our growth targets along the way we could do other things like downsize to reduce burn and extend the runway to hit our targets. The startup CEO’s primary jobs are not running out of money, setting the vision, and recruiting top talent. So the CEO goal is to not run out of money, which leads to a goal of raising money, which leads to a growth goal, which leads down into the team goals.

In the example above, you see how the CEO goals refine from not running out of cash down into growth goals required to raise a Series A. Then you can follow how the functional teams decompose this overall growth goal into their goals. I’ve left a big chunk of the bottom of the tree in each function undefined, because I want to talk about how the tree creates space for them to make their goals more detailed. For instance, product and engineering have clear goals around shipping weekly product and marketing experiments. Marketing has clear numerical targets that they need to hit based on these experiments. Product may want to adopt those because the product tweaks required to get a new channel working are on both product and marketing. Note that ops can play a role here — they can find ways to reallocate resources to put more firepower behind the company’s need to grow. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen ops totally divorced from the overall growth goals of a startup — adding to burn and building out “future proof” infrastructure that’s never used while the startup is understaffed in marketing, sales, product and engineering. Empowering ops to move the needle on product market fit and growth can be just the thing that unifies the company and stops misdirected bloat across all its functions.

In closing

Make no mistake about it, achieving your goals will be hard work. Setting goals is a lot more common than achieving them, and hopefully now you can see why. You need to clarify goals, visualize why we’re going after them, and work backwards to define leading indicators. Then you need to set and track milestones, and hold yourself accountable to results. Making faster progress often requires large behavior and organizational changes. We’ll also be wrong about some of our bets as to which leading indicators are going to move the lagging measurement of our goals, requiring us to shift tactics. It’s a lot of work and focus, but if we master it, we can achieve just about anything we put our minds to both personally and in our companies.