You can try to win, or you can try to make people happy, but you can’t do both

Paradoxically, trying to win leads also to making people happy, because people are happy when they win. Trying to make people happy in ways other than helping them win ends up making them unhappy, because they are less focused on winning, which is the thing that makes them happy.

In Cal Newport’s awesome “So good they can’t ignore you”, he expresses the general idea that people that are successful are passionate about what they do because they are successful at it, rather than being successful at what they do because they are passionate about it. In the same way, I posit that when you get teams focused on winning, they find passion in what they do, but if you try and get teams focused on what they are passionate about, then you wind up lurching all over the place and getting a lot of pet projects and shiny objects rather than focused harmonious team making magic together.

A lot of folks aren’t sure what makes them happy, and self-reporting is hard. So when you’re polling bottom up to try and find a path to happiness, you’re not necessarily even fishing in the right pond.

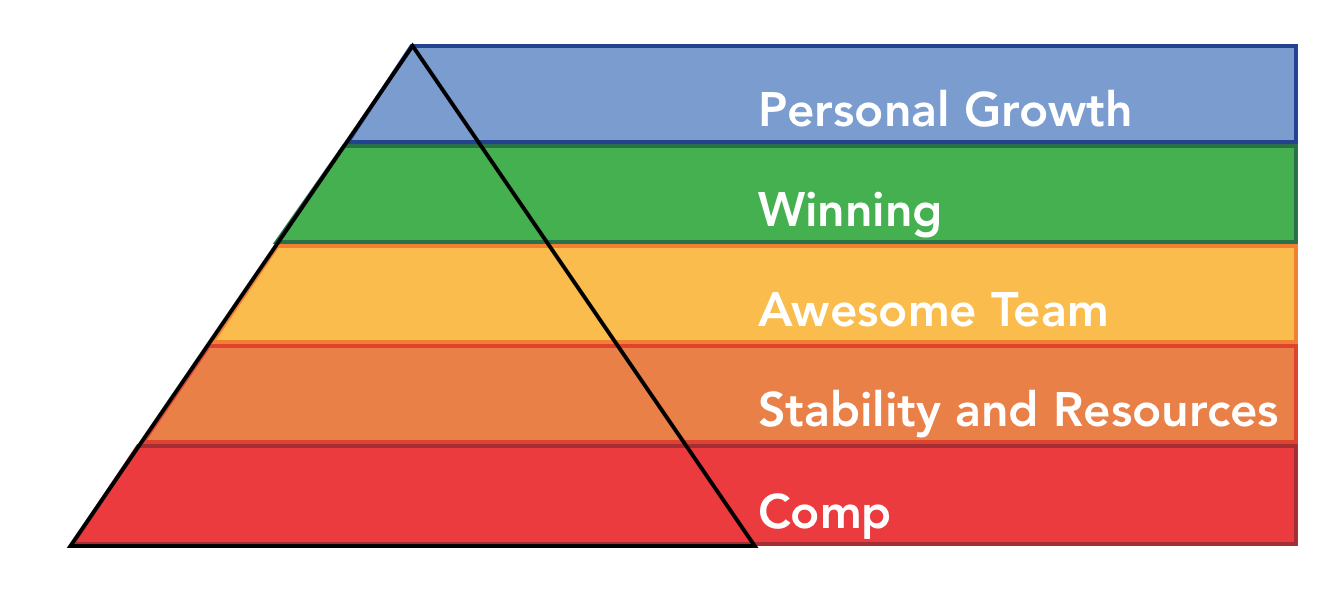

Professional hierarchy of needs

My friend Cameron Marlow first introduced me to the idea that there’s a professional hierarchy of needs that looks something like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. I’m naming the professional hierarchy of needs after him below, since he gave me the idea, and since Marlow sounds a lot like Maslow.

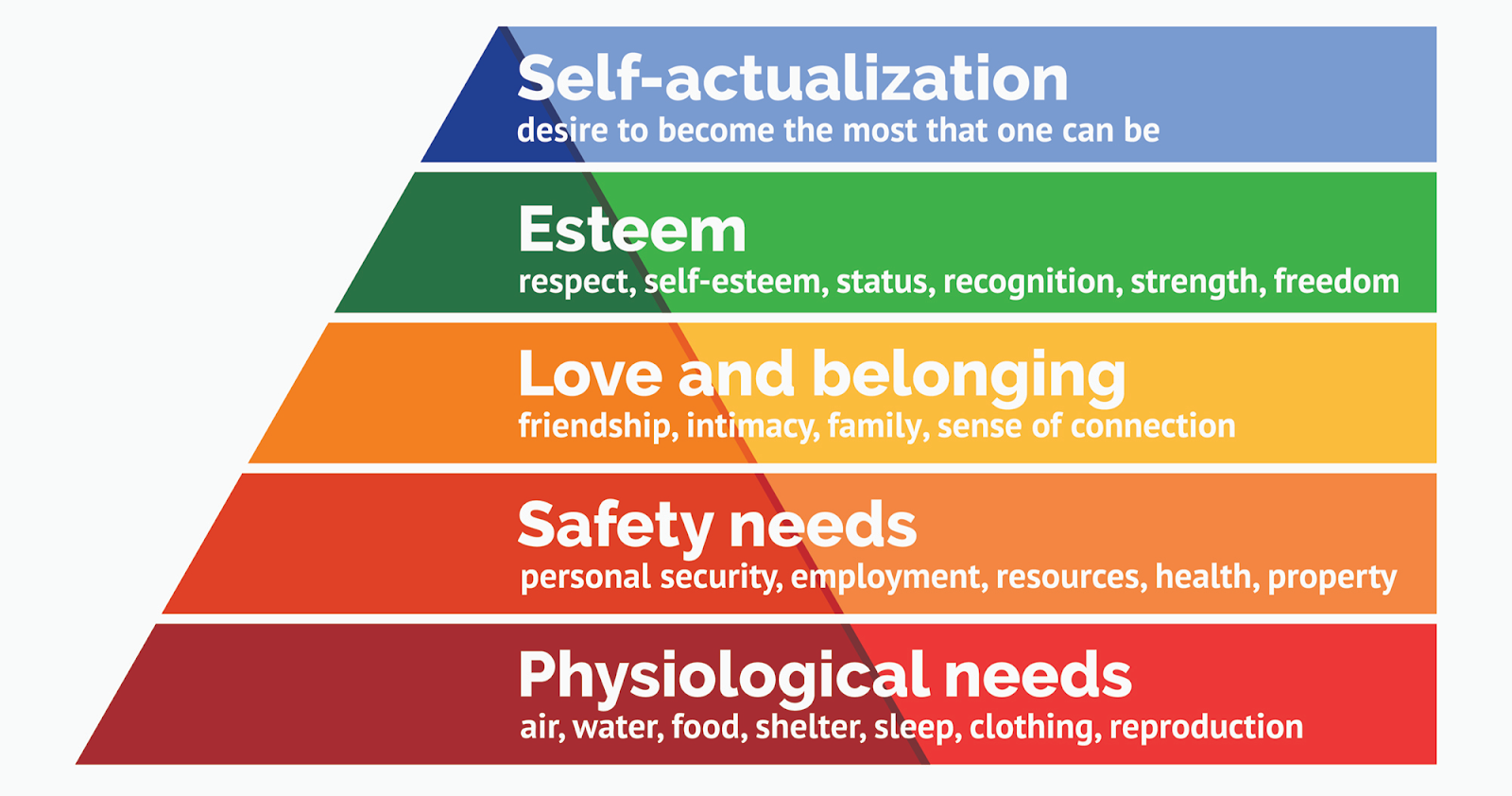

Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs

Marlow’s Professional Hierarchy of Needs

Most decent managers at least somewhat realize that, if you want to have a good team, then you need to pay good comp, provide a basic sense that the company, product, and team will continue to exist, and hire high capability individuals. However, many managers focus too little on winning and self-actualization, and too much on ancillary topics that generate a short term buzz.

Each level has some important parts to get right;

- Comp: Comp must be calibrated to be competitive to the market — you can’t say you hire the best people when you’re not paying the best. Comp also needs to be calibrated to stage and role; earlier stage folks should expect more equity and less cash, and variable como vs equity tradeoffs are important for sales.

- Stability and Resources: People need to have an honest sense of stability in their company, product and team. If there is too much existential risk, too much pivoting around and changing direction, or too much churn on the team, it’s just hard to focus and get things done. They also have to have the proper resources available to meet their goals or it’s demoralizing. Everyone likes to be pushed to do things they may not have thought they could do, but nobody likes to know they’re setup to fail in an impossible game. For example we can work extra hard but we can’t always figure out a way to do ten times the volume of work for a team out size. We can be extra creative but we can’t always generate tons of new customers without much budget for marketing and sales.

- Awesome Team: People need to have an emotional sense of community among their team, and this comes when the personal and professional aspects of the team are all healthy. We’re all capable, and any performance issues are being dealt with, so there’s no tension where we see some weaker members of the team that we might like as people but that we know are holding us back. We’re all excited to learn from each other because everyone is amazing and bringing something slightly different to the table. We don’t have toxic narcissists and assholes around causing chaos and making people feel bad. People work hard but don’t burn themselves out too badly — we have lives outside work.

- Winning: We all understand the company’s goals, the team’s goals, and our individual goals, and how we win at all levels. It’s important to never have a culture of esteem being defined in ways other than winning — if people are trained to derive internal status and recognition from things other than winning, then you’re just providing incentive to do things that aren’t focused on your goals. There are almost always optically pleasing things to do that are easier with shorter term payout than the often unglamorous things required in doing the primary work required to win.

- Personal Growth: Hiring hungry people with an ownership mindset means that everyone wants to grow and take on more responsibility. I take comp, stability, and team as givens — any good companies and managers need to do this well. This means that the most important way that great companies and managers differentiate are #1 winning, and #2 personal growth. So personal growth is the next highest priority for managers behind winning, and should therefore be the second most discussed topic in 1:1s. Managers are constantly helping their team find the work that jointly optimizes for winning and growing into new challenges.

As we’ll talk about in a bit, most of the magic of great management lies in the interplay between winning and personal growth.

The illusion of feel good management

There are a lot of mediocre managers who simply focus on the short term things that make teams feel a sense of enjoyment, thinking it will make teams happy. Often these activities fall under the banner of ‘culture,’ but they also show up in weak voting-based operating models — let’s effectively just let the team vote the roadmap so everyone’s doing the work they personally feel like doing. Over-investing in designing the office, or perks, or taking surveys from the team, or having the team vote on backlogs — all these things are aimed at trying to make the team happy in the immediate term, but they ring hollow in the longer term as the team seeks real self-actualization through winning and growing.

Feel good management may create a short term sense of enjoyment, but it pretty quickly wears off in the team isn’t winning and growing. First, the best and smartest people on the team can see that we aren’t really defining or hitting important goals, or they can see no space for themselves to grow into larger ownership and push themselves to be better. Then these folks leave. Gradually, others follow.

Feel good management without winning and personal growth opportunities for the team always results in attrition followed by failure. So if you aren’t winning and growing already, focus instead on that long before you focus on various culture and bottom-up initiatives. Start by building a culture that’s focused on winning and on pushing to get better in important ways for winning faster and more with even better skills. These two things are primary, and once established, there are certainly other important considerations that optimize for the team’s well being. That said, avoid managers who invest in culture and bottom-up feel good initiatives before establishing a culture of winning and growing.

Esteem; winning and goal trees

Teams grow their esteem by hitting their team and company goals. Individuals grow their esteem by hitting their personal and team goals.

Goal trees are just a hierarchical mapping of company to team to individual goals. Trees let individuals clearly see their impact on the company overall, and strengthen the sense of esteem through strengthening their feeling of ownership in team and company level wins. They also empower individuals to think more creatively about how to impact the company goals — the CEO may facilitate among the board and leadership team to define company goals top down, but a good management culture then empowers team leads to facilitate among teams to define team and individual goals in whatever way they see fit.

A great company culture puts strong weight on ‘nose for value’ from its managers and team members. Let’s say you have a junior marketing person who doesn’t really know what work to do in order to have impact, and that person is frustrated because they don’t have enough direction and they can’t sense their impact. If a manager takes over this report and starts by trying to make them feel good by allowing them to define their own work bottom up, they’re failing. For a while, this team member will appear to feel good and produce a flurry of work. However, none of the work will have impact, and gradually, the team sees it, the team member sees it, and eventually others around the manager will see it. Even when the person isn’t delivering any useful impact, this person will probably eventually leave, because they’ll see themselves as great and see the organization as the problem — and they’re right! The problem is that feel good managers don’t understand the company’s goals, their team’s goals, and how to help the individual set their goals so that they’ll have real impact. Additionally, with no realistic impactful goals that would have shown the junior marketing person that they have a long way to go in growing their skills, the team member probably hit some of their ill informed self-defined goals, were consistently praised and validated by their manager, and probably lost out on the opportunity to calibrate on what level they’re really performing at. Another company that seems more successful reaches out validating their sense of accomplishment, and they move on to another job — when meanwhile it was the case that the team member either needed to increase their impact dramatically or be managed out. This is the sequence that plays out commonly in companies without a focus on managers and team members having a strong nose for value.

Managing up to winning

If you’re a manager that sees that you don’t have a goal tree from the company to your team, or a team member that sees you don’t have goals for your team, then this becomes the #1 thing to raise with your manager in your next 1:1. I’ve never seen an organization that execute well without understanding its goals, so job #1 for everyone is to understand your goals.

It’s common that middle managers or line managers want to set goals for their teams, and their team wants goals, but the goals from above are unclear. Either the CEO or someone in upper management has failed to define clear goals, so nobody else can either. In this case, the way to show maximum ownership and initiative is to just define everything that’s missing and necessary to define your own goals. If the company goals aren’t clear, then state what you think they should be. If the goals for your region, group, or whatever entities are above you are unclear, then define those. Then define your team’s goals.

As an example, let’s say you are in a larger organization whose product is lagging behind some of the competition in the market, and not selling as well. You’ve been a strong sales manager, but now the bigger issue in the company is that we’re not just losing new opportunities to the competition, we’re also losing some of our biggest existing customers to the competition. So senior management has asked you to take over relationship management and focus on customer retention while the product is brought up to date. The trouble is that senior management hasn’t defined clear goals for existing relationships, and you think that your team shouldn’t just be looking to retain them on the product that’s being updated, but also to try and cross sell into other relevant products your team knows about.

You can just define what you think is a reasonably aggressive set of goals, such as not losing any of the top 50% of your accounts, and growing revenue by 5% through cross sales, and then sit down with your team to discuss and get alignment. You don’t want to give your team no direction and have them defining goals purely bottom up, but you also don’t want to come with already fully defined goals for the team without creating space for their input — this is the art of giving enough direction while creating room for team input, which creates stronger sense of buy in and ownership from the team, while still giving the manager space to push the team for the best performance they can deliver. Once you have the team’s goals ironed out, then you can show up to your next 1:1 with your manager and share your team’s goals and leading indicators to track retention and expansion, and you can share that you’d like to see such goals defined at a higher level as well, and suggest what those could be baked on your team’s view.

Self-actualization; Professional personal growth

Great managers are always jointly optimizing for winning as a team and personal growth among their team members. This means they always think about what the team’s goals are, what their team member’s goals are, and always coming up with clever ways to help the team get to the right work that maximizes their impact on the team goals and their progress on their personal growth goals.

A common example of this is to recognize and grow new managers and leaders. First, managers and leaders aren’t the same. Managers own team execution results and people management reports, leads tend to me more oriented in functional skill areas. Current managers need to be able to spot team members taking on more ownership proactively and naturally growing their authority within the team. Then they need to be able to help that person identify where they find the most joy and the highest impact on the team — is it more the type of work a manager would do or a skill-focused leader would do. Do they want to take on a regional manager role on a sales team, or an engineering manager role, or would they rather be the #1 grossing rep in the company owning specific deals, or be a tech lead for the core services that the company most depends on? Both sides of the coin are just as important to the success of the business, it’s just a question of whether one enjoys and is better at the execution or managing the execution.

I’m a fan of building a culture of the most rapid possible personal growth. That means the team is always hunting for more ownership and greater impact. As a manager that facilitates rapid personal growth for the team is therefore needing to enlarge the ownership and impact pie at all times, otherwise they can’t create enough space for the team to grow into. This is where it’s important to be creative — find ways to nudge the team to think about topics where they are strongest and how to find great amounts of important work to do there that directly impacts the team’s goals. An example would be someone in marketing identifying the need for, getting buy in for, and then defining a new tracking system alongside a few of their campaigns. This marketing person took the initiative to see something that would make the team better at meeting their goals, and fixed it for everyone while doing their own work. Another example would be an engineer that delivers a new feature while massively cutting down some gnarly legacy code. When the team complains about things in 1:1s, these are classic opportunities for the manager to encourage them to fix the things they’re complaining about.

Winning and growth in regular 1:1s

Normally people’s ideas for their own growth are expressed in how their personal goals map to the team goals, and maybe a couple other extra goals that grow their skills or well being, but not necessarily aimed at short term team goals.

I usually run 1:1s by first asking what’s on top of my team member’s mind, and if I have something top of mind, I’ll let them know that I want to cover that right after whatever is most pressing for them, and before we get into anything longer term. For example I’ll share any big strategic news such as fundraising, major sales or new customers, big new product changes, or team changes.

Transparency creates trust in an organization. Many companies think that the team needs to be protected from certain top secret strategic news, and that it will defocus them from their work. I believe the opposite — people are smart, they know what’s going on at a high level, and can sense if something is going really wrong or there are major changes coming. Misleading them or withholding information just makes them cynical with management — if management doesn’t think team members should know about critical strategic matters, that’s communicating that they don’t think team members would do anything useful with that information, and that it could even be net harmful. If your company has hired high initiative people with a strong ownership mentality, then you are just disempowering them by restricting their access to critical information that might lead them to make different day to day decisions about how they have the most impact on the company’s success. If management trusts everyone wants to help the company win, then they need to feed all possible information to the team to help them make the best decisions. A great example of this is M&A discussions. It’s often the case that management is worried about sharing this with the team, because maybe some people will quit, or be scared about the uncertainty, or maybe engineering won’t be shipping new features as fast. If management explains to a great engineering team why M&A might make sense at some point, and that the company is always open to hear about strategic opportunities that align in certain ways, then engineering might surprise management with leaning in rather than checking out. There will be technical due diligence during any M&A process anyhow, and an an informed and great engineering team will actually get ahead of this — they might hustle to ensure they can claim and present certain things about the system that they know represents the core value to would-be acquirers, giving management more firepower to push for higher valuation, better vesting terms for the engineers that come over in the deal, etc.

I like to create an open dialogue where mutual vulnerability is OK, so I’ll be honest if I’m doing really poorly or have exciting new news, and I’ll ask if I know they have anything major going on in their lives. Sometimes they will have major complaints or updates, and this is often a great opportunity for me to identify and steer them to growth and winning opportunities. Let’s say for example an engineer complains about something really messed up on the backend, and they are whining that everybody knows about it but nobody does anything about it. Then of course I’m going to encourage them to own it, and help them outline their plan right there and then during the 1:1, down to the detail of how they are going to kick off this discussion with other teammates to coordinate the big changes. Only at the end of the 1:1, if there’s time left, would I fallback to checking in on their more formal goals that map up to team goals. In this way, most of good management is this back-and-forth interplay between the immediate term things on the team and managers mind’s, the active work and issues coming up, and then ensuring that we’re doing the most important work each week.

A lot of the magic of good management happens in these 1:1s and more people-meets-execution interactions, and less in rolling out process and sitting in project management meetings. The reality on the ground is always some mix of project management combined with reacting to day to day issues that bubble up, all modulated by the motivation and focus of each team member. One key aspect is balancing the project plan against things that bubble up and may or may not require us to react, and this can often involve tricky on the fly prioritization decisions and tactical adjustments. Another key aspect is balancing the work to be done with the motivation to do it; the fastest velocity comes not from death march project management, but from individual team members finding the most challenging work for themselves to do, in the nearest direction of how they want to grow their skills, and in the nearest direction that will have the greatest impact on the team’s goals.

Sometimes people want to develop skills outside work, which would be education connected to work, picking up a new hobby, getting in shape, dealing with some life drama they want to put behind them etc. It’s important the manager is attuned to this and encouraging space for this too. If someone is getting burned out because they have no time with family, then help them learn to setup effective calendar blocks and shut off work for family time from dinner till they put the kids in bed.

Good managers are also making sure their team’s are healthy and happy — are people needing some time off, or maybe a clearer picture of work to do. Do they feel heard, and do they have the resources available to them to take the initiative to solve the problems they see? Is their mental health in a good space, or is there any support and encouragement that their manager can give.

Winning is not just about people focused on the highest impact work, but also maintaining a healthy team that can output with sustainable force. Personal growth is not just about doing the work that pushes your boundaries, but also growing personally and professionally more broadly. Great managers see people holistically, not as worker bees pulling the next task off the assembly line.

The new version of up or out

Many high performing organizations like McKinsey, Facebook, and the US military are known for their up or out policies. Team members have particular time frames to be promoted to the next level, or they are expected to transition out. This is especially common at the lower levels in the ladder, where there are often concrete 12-24 month expectations to move between levels.

I don’t believe in stack ranking, or referring to the top X% or bottom Y%. If you do a great job on hiring, and you are proactively managing to a simple leveling system, then you’ll naturally manage up top performers and manage out underperformers. You don’t really need to go into the further detail of stratifying everyone into quartiles of performance or anything — I generally think its a waste of time. If you have a basic leveling and comp system, then it’s simple; 1) someone is performing above their level, and they need a promotion and raise, 2) someone is performing within their level but getting better and should get a raise within the level’s comp bands, 3) someone is performing at their level but staying about the same, and their manager needs to talk about how to get them growing, 4) someone is underperforming at their level and the manager needs to think about a PIP or transition plan. If this is done well, then there’s no need to engage in more complex stratification during review cycles.

The #1 responsibility of managers is to win, and the #2 responsibility is to grow their team. Managers have to proactively advance people through levels, otherwise the best people start looking elsewhere and feel they need to switch companies in order to get promotions as quickly as their skills merit. Great managers aren’t just asking their teams how they want to grow as individuals, they are proactively identifying high impact people and emerging leaders, and coaching them towards the work that makes their impact even greater and their growth even faster. They are also masters of building and composing their teams — this means being great hiring managers. They spend a great deal of time with recruiting, and are always thinking about the right composition for their team. They know if they have too many senior people on the team and not enough room for their growth, and they know if they have too many junior people on the team and not enough leadership to give them direction.

The ultimate test of managing for personal growth is what happens when a team member outgrows their team. If a company and team isn’t growing its business, product and system complexity, and team fast enough to challenge all the fast growing leaders it has nurtured, a great manager is not afraid to graduate teammates into alumni status. There are also only so many C-level jobs and founders, so if someone needs to lead at that level and there’s not space in the team, then proactively helping them find that elsewhere is way better than losing key leaders by surprise. A great management culture creates super fast growth in skills and encourages initiative and puts pressure on the business to grow fast enough to keep up with its people’s desire for more ownership. For example maybe the engineering org is incredibly well managed and always pushing teammates to take on more responsibilities, but the product/market fit isn’t as good and the sales and marketing functions aren’t as strong, so that engineers are growing faster than the sales, marketing, or product team members. This reduces the workload and opportunity to scale engineering to take on new challenges. It might make sense for some engineers to seek opportunities elsewhere. A great manager isn’t afraid to help some folks find jobs elsewhere, and in fact they will help make introductions, serve as a reference, and coach them through the process. This controls inevitable transitions, builds trust, creates very positive vibes, allows the manager to help guide the balance of senior-mid-junior, and allows everyone to build stronger networks. Besides, a great manager is a master recruiter, and always has a strong pipeline of existing and newly sourced contacts to bring fresh energy into the team.